In Other Worlds

Dystopian fiction as literature of trauma, Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, Margaret Atwood, Suzanne Collins, and a reading update

Hallo it's me, Laura King. Ten years ago this weekend I graduated from UCD with an MA in Modernity, Literature and Culture. That sentence alone is odd enough for me to say and type, but I’ll spare everyone the reflections on the past decade of my life and instead revisit what I was reading, thinking and writing about at the time. It’s interesting now, with that distance, to think about the subject I chose for my thesis, which was an argument for viewing dystopian fiction as a kind of, or through the lens of, literature of trauma, with a particular focus on Brave New World by Aldous Huxley and Nineteen Eighty Four by George Orwell. Everything I read, or watched, in that year seemed to tie into what I was writing about, and in fact, by the time I was actually writing my thesis in the summer of 2012 the first film from The Hunger Games franchise had just taken popular culture by storm. These books had been a definite influence on me when I read them the previous year and combined with a critical theory module I’d just taken that semester on literature of trauma, it’s obvious now how I came up with this subject. If you have not yet read the writers I’m talking about here, think of those post War on Terror novels, The Hunger Games series, and keep in mind the violence and fear of that repressive society alongside routes to rebellion as you’re reading this newsletter.

Trauma fiction in the early stages of the term referred to novels written about particular traumatic events and their aftermath in an individual’s life, but by the time I was studying for my undergraduate degree, discussions about literature of trauma looked at patterns across all sorts of writing and was interested in how experimentation with language and structure could either represent that event, or create a new way of expression in its aftermath. Many of the writers I studied assumed that the weight or effect of trauma has, either on the individual writing the book or on the characters inhabiting that world, means that the language itself has to be somehow fractured or broken. This can be conveyed in a myriad of ways including repetition, indirection and dispersal of narrative voice.

I felt that this (relatively) new way of reading had endless possibilities in shining new light in works of literature where a kind of collective trauma or memory was simmering under the surface and was conveyed by the way in which the book was written, even if the content doesn't explicitly deal with this event. I loved thinking about how writers could deal with painful or shocking events in the collective experience, and how they could do this in experimental or challenging ways. In a paper I wrote for publication in my university’s journal at the time, I said that in dystopian fiction, the author invents a terrible, nightmarish world and sets it in the future. However, this invention is usually extrapolated from traumatic events of the author’s own time, judging the present moment. The novels I focused on are arguably the most famous dystopian novels, and were written after the events of the First World War, and in Orwell’s case, the Second World War. Anti-utopian, or dystopian, writing became very popular because the high hopes and grand narratives of wartime were unrealised and unfulfilled in the new peacetime and even more so, these ever more mechanized wars, with such horrifying death counts over such long periods of time, destroyed ideals held about progress and human nature. Wartime connects these dystopias and physical traumas and wounds, but trauma as a popular psychic concept also arose out of this time too with soldiers returning “shell shocked” from the battlefields.

It’s also no accident, to my mind, that bodily harm and trauma are at the forefront of dystopian fiction. Psychological control is achieved in different ways, whether it is the more (seemingly) “pleasant” social conditioning in Brave New World or outright terror of Nineteen Eighty Four, but the threat of violence or bodily harm is never far away. On the surface, most people would probably pick the pleasure-as-distraction of Huxley rather than the fear of torture in Orwell, but both feature totalitarian regimes that discipline and punish: one society is just further along in its mission to make that social control deeply ingrained than the other. It’s always interesting to me that the scenes that feature the most violence or are the most disturbing are the hardest to read and follow, and the use of that fractured, disjointed language is a perfect example of the kind of writing that fits so well with literature of trauma. I concluded that study by pointing out that, while the body in pain is the most striking image of those novels, the glimpses of survival are seen through the body too, by a return to human nature and the natural world, and the acts of love or desire are the most transgressive in those worlds run on fear.

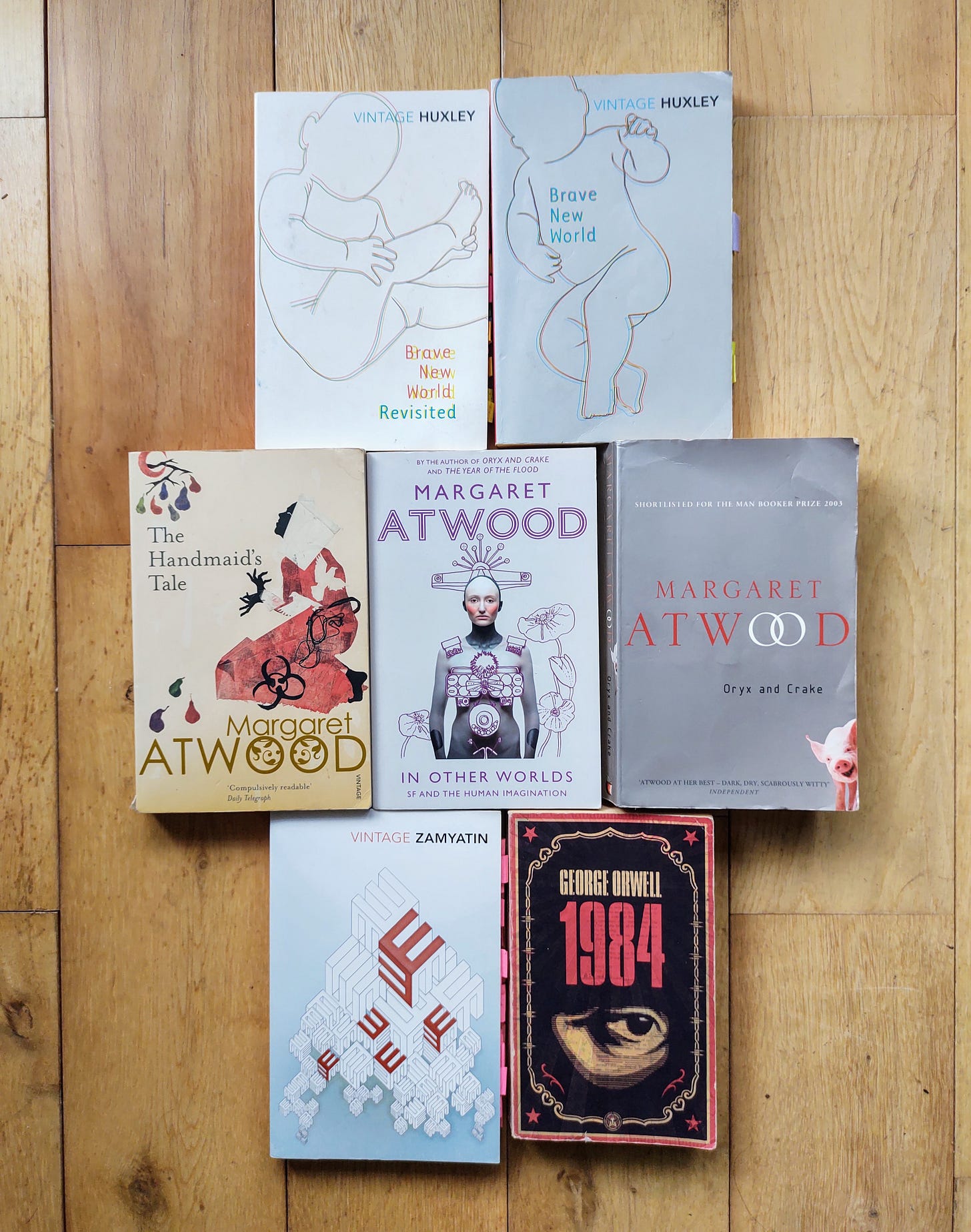

When you look at the novels as part of a genre, it’s interesting how different books written before and since the two I focused on all are linked by post-war trauma and fears about the future of the human race in the wake of all this violence. I’m surprised time and again how similar types of social control and punishment crop up in so many books in this genre, and how descriptions of the body in pain are almost always rendered in slightly more indirect or shadowy ways than the rest of the work. Orwell was really influenced by Huxley, and Huxley in turn wrote Brave New World Revisited thirty years later reflecting on his original novel in light of how the world had changed, as well as his reading of Nineteen Eighty Four. Yvgeny Zamyatin’s We, a Russian novel banned on its publication in 1921, is a disturbingly prescient and brilliant novel that I feel is often overlooked, and is often cited as the first modern dystopia and a reference point for both Huxley and Orwell. In We, a citizen of the “One State” is torn away from his obedience to the “collective” good - again, rebelling by falling in love and choosing individual liberty and human nature despite the punishment he knows will surely follow. So much of that novel, in turn, reminded me of The Hunger Games and particularly its conclusion in Mockingjay, when I read it ninety years after We was first published. In a regime that runs on the spectacle of violence as a means of social control, Katniss can never really tell what is real, or not real, and her only moments of certainty are when she encounters extreme feelings of pain or love, and the only escape is through a wilderness outside of the reaches of the government.

These writers took their history and how it affected the present moment, and from there imagined a horrible future that was grounded in real events and concerns from their time. I believe this is quite commonly accepted as true, now, but still quite lazy discussions about utopias and dystopias persist, where people talk about books that “came true” as if by the psychic powers of the author, rather than how cleverly that author imagined the future based on real, past events. Margaret Atwood has spoken and written a lot about this in the past, most recently after the second success of her novel The Handmaid’s Tale, the recent television adaptation of that book and the follow up novel The Testaments. Atwood refutes questions wondering if she’s a witch (though she may very well be one) and always reminds people that everything in her original, groundbreaking novel The Handmaid’s Tale was inspired by real life events, somewhere in human history. As if the story of a not-so-distant future of a repressive society where many women are kept in rich households to carry the children of their oppressors, was not terrifying enough, it’s worse still that every act of terror and violence is a direct reference to something that once happened in our world.

If The Handmaid’s Tale is Atwood’s Nineteen Eighty Four, her Madaddam series, beginning with Oryx and Crake, is her answer to Brave New World. In the first installment of this series, The Snowman, previously known as Jimmy, goes out in search of other humans after a plague that has wiped out so much of humanity. He is accompanied by a new breed of species that have only known the lab where they were born. As in Huxley’s novel, in Oryx and Crake, the natural world and bodies are changed irrevocably, and the world was changed by impulses people are too used to ignoring: greed and ego masquerading as "progress" in general, and uncontrolled developments in genetic engineering more specifically to this book. I’ve often wished this trilogy would get the same worldwide recognition as her other dystopia, especially now as this alternative but equally chilling vision of the future begins after a plague, which seems all the more relevant since 2020. The theory I keep coming back to is that The Handmaid's Tale, like Nineteen Eighty Four, has clear roots of evil that you can point at and name, whereas things are more difficult to pin down in Oryx and Crake and Brave New World because the regime is so advanced that it has changed humankind and Planet Earth so completely over years. In both works by Atwood, the use of repetition, indirection and a fractured or unreliable narrative voice points to literature of trauma as a starting point to better understand these dystopias.

No one dystopian novel is “right”, because the world and the future is always changing. Some types of dystopia can be more popular with some readers than others depending on what is happening in the world, and the viewpoints of those readers change too over their lifetime. I unfortunately discovered Atwood’s non-fiction book In Other Worlds: Speculative Fiction and the Human Imagination just after I finished my masters thesis, and I was initially frustrated since she explained so perfectly what I’d been trying to capture for so long. However, I ultimately loved this book not for its usefulness in a project but because it spoke to my own, more personal feelings, about reading and the imagination. She calls this book “an exploration of [her] own lifelong relationship with a literary form, or forms, or subforms, both as a reader and a writer”, recalling the imagined worlds she created and inhabited as a child. She writes, in a sentence that has never left me in the decade since I read it, “our earliest loves, like revenants, have a way of coming back to us in other forms: or, to paraphrase Wordsworth, the child is mother to the woman”. Just like the stories she wrote about monsters and aliens gave birth to the groundbreaking dystopian, or as she calls it speculative fiction, that she’s famous for, the way I think about reading and the imagination is rooted in how I accessed the real world through fiction as a child too.

Whether it is science fiction, or fantasy, or dystopia, or some other form that takes its influence from our real world to imagine another one, it’s easy to follow those roots back to its source, and use the book as a kind of mirror to see reality somehow more clearly than we can with our own two eyes. I understand what people mean when they say that they choose to read fiction as an escape, or a distraction, from their own lives or the world around them, but the opposite has always been true for me. I read to see my own self clearly, to see the world more clearly, and though I don’t read as much science fiction or fantasy as I used to when I was younger, these fantastical worlds never feel too far from reality for me, knowing where they come from. Because of that, I never think of reading as much of an escape, but rather as that mirror: wherever you go, there you are.

Reading Update

Physical book: In much cheerier news, I’m reading Anne Enright’s tender and insightful book of essays from 2004 on motherhood, Making Babies, and chuckling along with a more indulgent and gently humorous Enright than I’m used to.

e-Reader: I don’t know what I’m at with my eBooks at the minute but I did start Honey and Spice by Bolu Babalola which is a clever and funny romance set at a university.

Audiobook: I’m still going with Tell Me What I Am by Una Mannion and I’m really hooked now, so I’ll have to go on a few extra walks to make sure I can finish it this week and find out where it’s going.

Next week I plan to write a bit about books and bookish gifts for Christmas, so please feel free to reply here or directly message me on Instagram with any requests and if I can I’ll answer next week, in another installment of LauraEatsBooks… Stocking.

This is a great piece